A year into the Zika epidemic in Brazil

Defining congenital Zika syndrome has not figured out all the uncertainties that still surround the condition.

A year ago this Friday (Nov. 11), one of the biggest epidemics in Brazil officially emerged. On November 11, 2015, the Ministry of Health declared a state of Public Health Emergency of National Concern. It was then two months since doctors in Northeast Brazil had raised concern about the large number of babies born with microcephaly in several states.

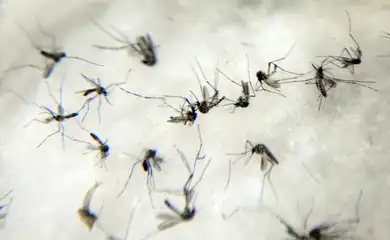

That marked the beginning of a long, agonizing saga for mothers, pregnant women, and their families, trying to figure out what was going on. Researchers across subject areas eventually concluded that the microcephaly cases might have a connection with a new virus carried by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Zika became the ultimate health concern in the country.

Infectologist Antônio Bandeira provided care to the first patients with symptoms of a virus that was still unknown in the country.

Discovery

The first cases of Zika infection in Brazil occurred in mid-April 2015 in Camaçari, a city in the metropolitan area of Salvador, Bahia. Infectologist Antônio Bandeira provided care to the first patients with symptoms of a virus that was still unknown in the country. “I was struck by the very large number of patients with the same symptom in the emergency room. Skin rashes, mild fever, pink eye, and pain all over the body. It was as if people were photocopies of one another,” the doctor recalled.

The patients tests from Camaçari were sent to the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), where they were examined by virologists who found the presence of Zika virus and verified its transmission by the vector mosquitoes. “Virtually all of those samples were positive for Zika, so we were facing the first reported outbreak of the virus in the Americas at that time. We promptly notified it to the Ministry of Health on April 29.”

But not all patients experience the symptoms of the infection, and the red flag was not raised until the second half of 2015, when adult patients emerged with Guillain-Barré's syndrome and hundreds of babies were born with microcephaly, especially in Pernambuco.

Zika and microcephaly

The connection between Zika virus and microcephaly was discovered by researchers at Professor Joaquim Amorim Research Institute (IPESQ) in Campina Grande, Paraíba. “We in fact added to research that was already in progress in Pernambuco where some researchers had considered that possibility, but didn't find the virus. We succeeded in detecting it in amniotic fluid and discovered it was the Asian virus that was circulating here in Brazil. It's much more aggressive and tends to attack the central nervous system,” says neonatal specialist and IPESQ Coordinator Adriana Melo.

The issue was not yet prominent in the media when Elaine Michele, 29, started to get signs from her body of what was to change her life. She lives in São Lourenço da Mata, a city in the metropolitan area of Recife, Pernambuco. As its name suggests, the municipality is surrounded by a forest, a factor that combined with poor sanitation to favor the proliferation of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

Elaine, the mother of 14-year-old Eduarda, was pregnant with her second child. What she could not have imagined was that her dream would be shaken by an epidemic. In the third month of pregnancy, she woke up with rashes all over her skin. They quickly receded, but produced lasting effects on her life. The eight ultrasound scans she had during prenatal care were not enough to show calcifications in the baby's brain, which were only discovered when the baby was born.

Elaine Michele's son is among the confirmed cases of microcephaly caused by Zika.

“I had color doppler, 3D ultrasound, and nothing ever came up. But when he was born, it was a real blow to me. I was devastated. It was God most of all and my husband that gave me a lot of encouragement. I couldn't accept it at first. I asked myself why me? Why was it happening to me? I felt I was alone because I didn't know there were so many babies like mine. I didn't know about microcephaly as I know today, so I thought it was the end of the line,” Elaine recalled.

According to the Ministry of Health, between October 2015 and October 2016, 9,953 cases were reported as microcephaly and other nervous system malformations throughout Brazil. Of this total, 4,797 cases were ruled out and 2,079 were confirmed. Another 3,077 potential cases continued to be investigated until October 22. Of the total confirmed cases (2,079), 392 tested positive for Zika virus. The ministry, however, believes most mothers whose babies were definitively diagnosed with microcephaly had been infected with Zika.

Late diagnosis

There are three types of tests that can detect the virus, but only the so-called PCR (which stands out for polymerase chain reaction) is available from the public health service. The rapid tests that take 20 minutes to detect if the patient has ever been infected with Zika are ready to be used, but they are not yet available from the government-funded healthcare system (SUS). The ministry announced it was going to distribute 2 million kits by the end of this year plus 1.5 million by February 2017. Meanwhile, many women only find out they have been infected with Zika virus after their babies are born.

The cases are underreported because of the difficulty carrying out tests. Fast, accurate diagnosis is still a challenge, says Professor Antônio Raimundo of the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), who heads Roberto Santos General Hospital. “The biggest challenge is the testing itself. We've had issues with RT-PCR, a very expensive test that has to be done three times.”

Infectologist Antônio Bandeira is also facing difficulties. “Unfortunately, Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are spreading three viruses and we need better diagnostic systems.”

Research investment

A year after the outbreak, experts have admitted that the effects of Zika virus can go far beyond microcephaly. “This virus has already been associated not only with microcephaly, but also with a series of congenital defects and neurological complications that today make up what we call the congenital Zika syndrome,” warns Melânia Amorim, Professor of Gynecology and Obstetrics at the Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG).

But defining congenital Zika syndrome has not figured out all the uncertainties that still surround the condition. The Research Institute of Campina Grande is now working on investigating babies with microcephaly that have been infected with Chikungunya virus, as well as suspected cases of infection with other viruses. They are facing hurdles obtaining funding to complete the research.

“Everyone's kind of volunteering, no one's got a research grant. We're underfunded. We've been lucky to have our partnerships both with the city government and private colleges which have helped with diagnosis, and most of all, with the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, which has been sending us all the reagents for our research. Otherwise our arms would be folded by now,” says IPESQ's Adriana Melo.

Roberto Santos General Hospital, one of the largest in Salvador's public network, has also been doing research on the virus and struggling for investment. “We have no question that there's a link between Zika virus and microcephaly. But the more we study, the more questions arise. Why? Why is it so severe? When are the risks highest? Is there a connection with a history of infection with another virus? So we are starting research projects to answer some of these questions. Now we need to understand how to prevent it. What do you do if you have Zika and you're pregnant? We need more research to figure it out. We need funding, Brazil has to invest in science and technology,” says the hospital's director, Antônio Raimundo.

Translated by Mayra Borges

Fonte: A year into the Zika epidemic in Brazil